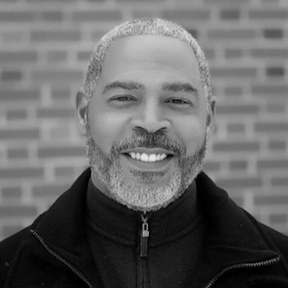

A profile of Staff Attorney Eric Williams—Economic Equity

Casey Rocheteau: How did you come to work for DJC?

Eric Williams: I bumped into Amanda at the Urban Consulate when she was on a panel there a number of years ago. She was describing DJC and I told her it sounded amazing. I told her when she finally put it together I wanted to work for her. When she put it all together, I applied, and here I am.

CR: That’s pretty straightforward. What drew you to the organization, and what were you doing prior to working at DJC?

EW: I started out at a large firm in New York, and my clients were cigarette companies, insurance companies, and banks. At a certain point, I realized I was the devil’s handmaiden and decided I had to change. So for the seven years prior to me coming here, I worked at Wayne State Law School and ran their small business clinic. I really enjoyed that. I liked working with the students and we helped entrepreneurs in Detroit. I can still walk down the street and bump into people whose businesses we helped start five years ago and they’re still up and running, and that’s great. There are local food businesses and barbershops. I just eventually found that it wasn’t as fulfilling as it should be. I initially went to law school to be a public defender, but the Kings County Public Defender’s Office wasn’t hiring when I graduated, so I ended up at a big firm. I wanted to do something that was meaningful that would help Detroit. I wanted to work not only with individual clients, but to affect systemic change on issues related to economic equity. It struck a chord with me. Having a background in business law and being able to put those skills to use for clients I care about towards a purpose I believe in was a no-brainer from my point of view.

CR: What’s your connection to Detroit?

EW: I grew up here, my family’s been here for generations on my father’s side.

CR: So you went away to law school in New York, what drew you back to Detroit?

EW: I had been trying to get back home for years. I moved away because I got married, and the woman I married lived in New York, and in 1996 Detroit was kind of a hard sell. Her family was there, so I moved there. I had been trying to get back for years, though. It’s home, and it’s a place where I genuinely care what happens here, to the people here. One of Detroit’s biggest problems is that too many people that could make a change moved away, so I just thought it was time to come back.

CR: Can you explain a little about eco villages and community land trusts, and the things you’re working on?

EW: There are a number of projects that have come to our attention because they’re rooted in addressing affordable housing, which is pretty important. If you take what people consider affordable housing, it might be about 80% of average median income—that’s the number used by HUD, but it’s derived from looking at the average median income of Detroit, Livonia and Warren. If you look at the average median income of just Detroit, it’s almost half that other number. As a result, what gets considered affordable housing in Detroit is higher than what market rate is in most of the city. The problem in Detroit is that you had white flight for years, and then when Detroit bottomed out, you had black flight. So, regardless of race, anybody who could move out of Detroit did.

The policy now is not to address poverty, but to address population. From most policy makers’ view, the problem in Detroit isn’t that there are too many people who are poor, it’s that there’s too great a percentage of poor people. This means that most policy is geared towards bringing people into the city who aren’t poor, figuring that if we can get the population large enough, the number of people who are below the poverty level will fall in line with most other cities. If you look at most of what’s happening, alleviating poverty isn’t a policy objective. When it comes to housing what that means is developments that are destroying naturally occurring affordable housing. As part of creating a just city, one of our objectives is to stabilize neighborhoods, preserve naturally occurring affordable housing and maintain it for future generations. There are a number of different ways to do that, and there are many projects underway right now that are attempting to do this. Some of the approaches involve creating an ecovillage, which is really exactly what it sounds like—an intentional space designed in infrastructure and operation to be sustainable. Other ways of going about this include using different legal structures to prevent rapid gentrification and increase in property values or increasing community input into development. For example, community land trusts allow communities to create and preserve affordable housing by separating the structures on a lot from the land itself. Since gentrification and increases in property values are typically related to location, i.e. the land, as opposed to what’s on it, having the land held by a nonprofit organization means you can avoid rapid gentrification because if a person sells a home, the next person isn’t buying something that’s increased in value by $35,000 over a few years.

We’re also working with community groups that are supporting or part of neighborhood advisory committees as part of the Community Benefits Ordinance. To the extent the CBO can be effective, there’s often a lot of confusion around the process, or what they can do, or how to work effectively as a committee. One of the things that we’ve done is put together a toolbox for the people sitting on the neighborhood advisory councils to be more effective from the jump. It includes everything from explaining how to put together the committee, Robert’s Rules of Order, how to put together an agenda, and giving examples of what they reasonably can and can’t ask for. It also has a piece about how to communicate with the public most effectively, which is one of their biggest assets, being able to bring to bear public pressure. This is a series of documents we’re hoping to host online to empower communities to use the Community Benefits Ordinance to their advantage.

CR: This is a silly question, but…best chicken wings in Detroit?

EW: I am very partial to Sweetwater’s.