A LETTER TO MY YOUNG NIECE ABOUT STAYING TRUE TO YOUR GOALS, DERIVING SUSTENANCE FROM NATURE, AND OTHER INSIGHTS I’VE GLEANED FROM ACTIVISTS. BY AMANDA ALEXANDER

Dear Fiona,

Last summer your mama asked me a question that I couldn’t shake. We were at a rally called by brave young people who are fighting for well-funded and safe schools, without police, in Detroit. If they win, you will never know cops in your schools. You may even think it strange they were ever there.

Our people were in the streets for more than 150 days last summer and fall. We’ve been in the streets since police killed Aiyana Stanley-Jones in 2010, since they killed Sean Bell in 2006, since they killed Amadou Diallo in 1999, and long before. As we were leaving the demonstration, your mama asked me: How do you stay focused on Black joy and liberation? And how can I raise my child with that sense of possibility? I didn’t know how to answer her in that moment, but I promised I’d give it more thought.

These are some of the insights I’ve kept close through 20 years of movement work. It’s basically what all of my life has been aimed at honing. I’ve learned these ways of being from elders, writers, and organizers — sometimes in community and sometimes alone. I’ve gleaned the most from Black women philosophers, prophets, community builders, and strategists who cultivated young leaders and ensured that movements could sustain themselves across generations.

When my mama died at age 60, I decided that I wanted every aspect of my life to come alive with color. And that I couldn’t numb myself with work — even noble work — or delay joy and pleasure. I’m sharing what works for me more days than not, with the hope that it might hold something for you.

Focus on the movement builders.

Whatever the problem is, there are people resisting, being creative, and finding solutions. Across the country, people are defending themselves and their neighbors against eviction and deportation. Organizers are blocking new jail construction and shifting millions of dollars into health care. People are putting their hands back in the soil, growing food, and building resilient local economies. People are creating a better world right now, and we can learn from each other.

Find what brings you joy and put it to use for movements.

It’s important to come out to demonstrations and protests if you’re able. But when the task is ending mass incarceration, making policing and prisons obsolete, and creating conditions for all people to thrive, the problem is so deep that there’s work for everyone all the time. Everyone can be part of the solution. Cooks can feed and fuel the movement, as Georgia Gilmore and the Club from Nowhere did in Montgomery. Architects can refuse to design torture chambers. Mathematicians and data scientists formed Data for Black Lives because they were tired of seeing things they loved — math and data — being weaponized to redline, police, and exploit Black communities. We need artists, healers, teachers, parents, carpenters, and scientists. Everyone has a role to play.

Practice your freedom.

While we fight to be free, we must also practice our freedom. Most weeks I take a tech sabbath. I stow my phone and laptop away. I sit at my dining room table and write across the top of a sheet of paper: Today I want . . . And then I listen. I only write down things I truly want — I know because I can feel the excitement shooting down my arms as my hand moves across the page. This practice reminds me of who I am, what matters to me, and how I feel most free: Today I want to go for a walk through tall trees. I want to hear my friend’s voice. I want to learn how to pinch the zinnias back so they bloom with more flowers. This keeps me in the habit of being guided by my intuition. I understand what it feels like to be free, and how to sort that out from obligations or the imposition of someone else’s will on my own.

Once I’m in touch with what it is I truly want, I can ask: What would it feel like for my wildest dreams to come true?

Lorraine Hansberry inspired me to do this. In 1960, the Black queer playwright and revolutionary — whose first play, when it opened on Broadway, depicted Black people with truth and complexity and allowed Black actors to play dynamic roles for the first time on that stage — made time to write lists of her “likes” and “hates.” When I first read them, I was struck by how well she knew her interior world. It’s that kind of knowing that makes it feel possible to love well, in every sense. By knowing what I want, I can communicate what I feel, want, and need. It keeps me from substituting another’s desires for my own.

Define the future worth fighting for.

Despite what many well-meaning people would have you believe, the question of our day isn’t “How do we end cash bail?” or “How do we keep police from shooting Black people?” Instead, it’s the same question that freedom movements have posed for generations: “How do we expand Black joy and liberation and ensure that all people and the planet can thrive?” Or, as I’ve been thinking of it lately, how can we have all the elders we’re supposed to have? How can we create conditions that allow us — all of us — to delight in watching one another grow old?

We have to be clear about what victory is and isn’t — and we have to insist on what freedom must mean. Rosa Parks was clear that she was never an “integrationist.” Integration wasn’t the point; her ultimate goal was to “discontinue all forms of oppression against all those who are weak and oppressed.” After she was blacklisted in Montgomery, Mrs. Parks came north to Detroit and worked on housing and community development, including helping to build the only Black-owned shopping center in the country in the early 1980s. If you know you’re working to cultivate Black freedom, you’ll have less patience for all the noise that’s beside the point and can direct your energy toward truly transformative change, in yourself and in the world.

Remember that this is intergenerational work.

Years ago, Mama Lila Cabbil, a lifelong activist, asked a roomful of us here in Detroit, “How are you building on the wisdom of three generations back, and passing wisdom forward for the next three?” Another activist I admire prides herself on never showing up alone; she always has younger activists with her.

Recognizing movement work as intergenerational helps us use our full imaginations. It can keep us from getting stuck in only reacting to everything the White House or others in power are doing today. We must fight like hell against repression and show up for people who are being targeted. And we must focus on what we want to create in our communities and what we’re building up over the long haul.

Notice and cultivate beauty.

I was raised by a mama who taught me how to seek and cultivate beauty. She was exceptionally curious, especially about people and plants and what might make them happy. I feel her presence all the time, especially when I’m walking a trail and noticing the grasshoppers, milkweed, and wild roses. My aunt described my mom’s way of mothering so well: “She held her child up to the world, and the world up to her child, and said, ‘Isn’t it amazing?’” My mama was my field guide to this miraculous world, and she showed me the through line from curiosity to compassion and care.

Go to places that make you feel like a tiny speck.

Mountains or ocean or a sky full of stars keep everything in perspective.

Build community through curiosity.

I’ve found that better conversations come from asking better questions. I try to invite people into the types of conversations that grow our souls and that will reverberate through time — just like the question your mama asked me. Some of our greatest movement builders knew this and they had core questions they asked of everyone they met. Ella Baker would ask, “Who are your people?” Grace Lee Boggs would ask, “What time is it on the clock of the world?” I try to think about what this person can teach me that no one else can.

Affirm courage when you see it.

When someone speaks courageously and generously from their heart, they honor us all by showing up that way and saying what needs to be said. Thank people when they do that. And be the first to be brave when you can.

Admire ease, not just struggle.

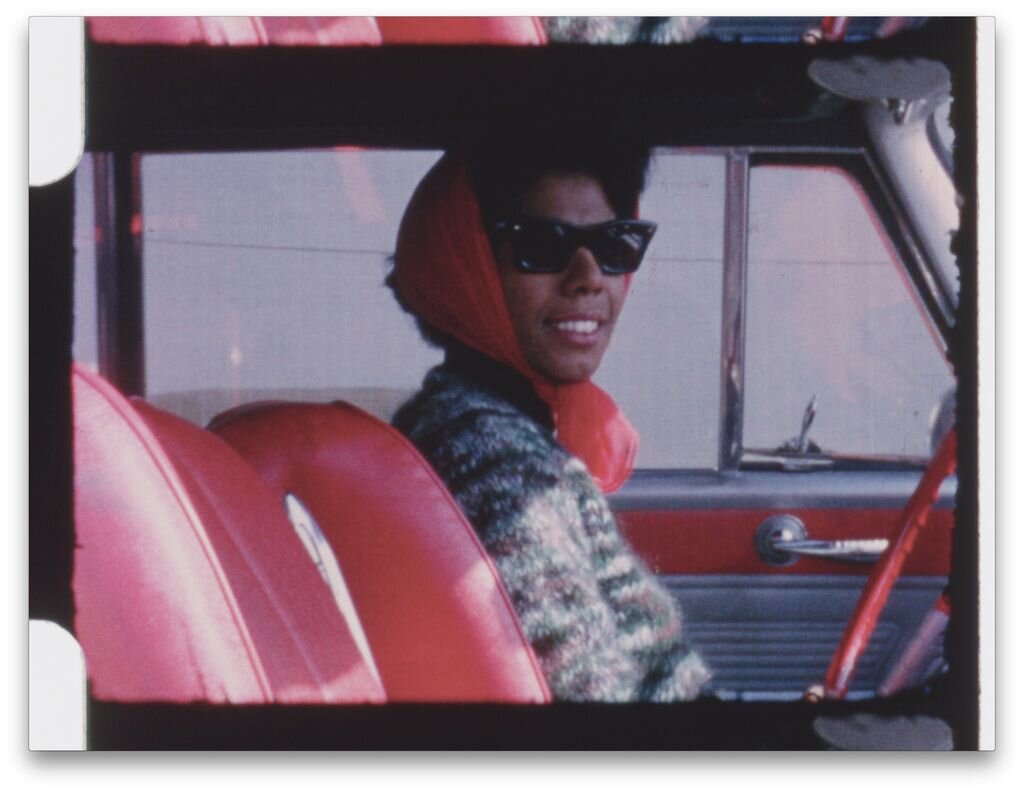

I try to admire our great movement builders not just for the moments of confrontation that are seared into our collective memory but also for their ease. I love the photo of Rosa Parks doing yoga. And images of Toni Morrison sitting by the water. I love knowing that their souls knew peace. I love knowing that Toni Morrison loved a good party. There’s a reason that a photo of James Baldwin and Freedom Rider Doris Jean Castle dancing together feels so good. They’re delighting in each other’s freedom and their own. We need to see and celebrate — and create — these moments of delight, and not just honor the struggle.

We are never alone.

You are part of a creative legacy that renews itself each generation and each day. This cycle of love surrounds and protects you always. You honor it by being yourself.

Love,

Aunt Amanda

(This letter originally appeared in The Boston Globe’s Ideas Section on February 11, 2021)